The Duarte family was a Jewish-Portuguese (Sephardic) family. Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492; in 1497 they also had to leave Portugal or convert to Catholicism. The Duarte family chose the second option. But the Portuguese Inquisition continued to persecute these 'conversos'. As such, the family decided to move from Portugal to Antwerp in the second half of the 16th century. Indeed, Antwerp was a prosperous and relatively tolerant city. The Duartes seized the opportunities offered by the port city, with both hands.

Diego Duarte (I)

Around 1570, Diego Duarte (I) (Lisbon?, c.1544 - Antwerp, 1626) came to Antwerp from Portugal. In Antwerp, he was part of the Nação or the Feitoria Portuguesa de Antuérpia, the Portuguese Trading Company of Antwerp. Spices and other goods from the Portuguese colonies came to northern Europe via this trading company. Diamonds and pearls were also among the goods traded. In Antwerp, Diego built a trade in jewellery and precious stones. A successful one.

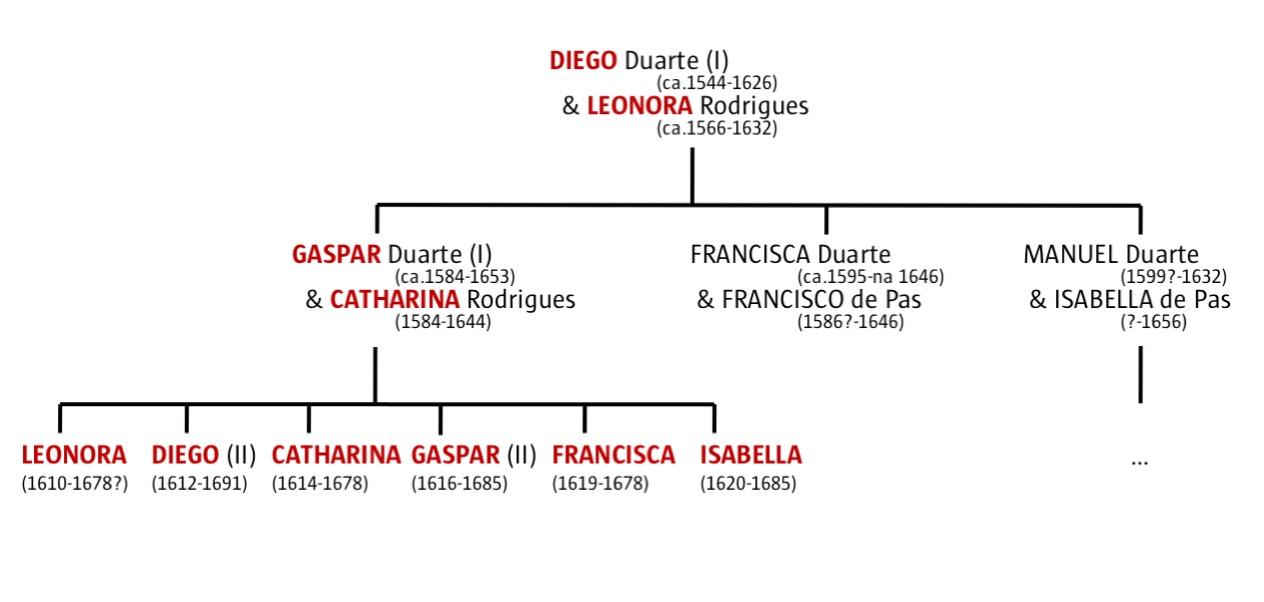

Diego Duarte (I) married Leonora Rodrigues (?, c.1566 - Rotterdam, 1632). Together they had several children, including Gaspar (I), Manuel and Francisca.

Diego (I) died in 1626. He is buried in front of the high altar of Saint James' Church. The grave became the Duarte family tomb. Diego had himself referred to as Portuguese on the tombstone.

A Dutch branch

Diego's eldest son Gaspar (I) (see below) lived in Antwerp throughout his life, but two other of Diego (I)'s children and Leonora moved to the Republic (the Netherlands).

Manuel (Antwerp, 1699 - Amsterdam, 1632) moved to Amsterdam around 1625, started a family there and returned to Judaism. His Jewish name was Ymanuel Abolais. This Duarte was also a jewellery dealer in Amsterdam. His sons-in-law had an impact on Jewish life in the Low Countries: Joseph Athias was a leading Hebrew printer, and the jeweller Manuel Levy Duarte was a director in the Portuguese Synagogue of Amsterdam, and he helped set up the Portuguese Synagogue at The Hague.

Gaspar and Manuel's sister, Francisca (Antwerp, c.1595 - Alkmaar, after 1646) also moved to the Netherlands. She was very musical and joined the so-called Muiderkring, a loose group of friends around the poet P.C. Hooft, which also included Constantijn Huygens and Joost van den Vondel. Contemporaries called Francisca 'the French nightingale' on account of her beautiful singing voice. P.C. Hooft dedicated a poem to her (freely translated). 'Frankje ... 'Thou makest, with thy song, the sheaves from below, ascend to heaven.'

Gaspar Duarte (I)

Like his father, Gaspar Duarte (I) (Antwerp, c.1584 - 1653) was a dealer of precious stones and jewellery. His commercial spirit brought him prosperity as well as power: in 1641 Gaspar became consul of the Portuguese Nation in Antwerp. The same year, he negotiated with Dutch diplomat Constantijn Huygens for a jewel that William II of Orange, son of the Stadtholder of Holland, would give to his future wife Mary Henrietta Stuart, daughter of Charles I. Anthony Van Dyck depicted the jewel on the wedding portrait of William and Mary (Rijksmuseum). This interaction was the start of the warm ties between the Huygens family and the Duarte family. They corresponded with each other throughout their lives, with music being their favourite subject.

Gaspar was married to Catharina Rodrigues (1584-1644). Together they had six children: Leonora (1610-1678), Diego (II) (1612-1691), Catharina (1614-1678), Gaspar (II) (1615-1685), Francisca (1619-1678) and Isabella (1620-1685).

In 1615, Gaspar (I) purchased a city palazzo on the Meir, between the Kolveniersstraat and the Otto Veniusstraat. It was the ideal home for his growing family. According to English diarist John Evelyn, the residence was 'regally furnished', while French diplomat Balthasar de Monconys, when visiting the garden, "saw the most beautiful orange trees' 'you can imagine'.

Gaspar (I) was known as a great lover of the arts. In 1623, he joined the chamber of rhetoric De Violieren. He donated an expensive costume to his fellow rhetoricians for a performance of the play Sophonisba Aphricana by Guilliam van Nieulandt (van Nieuwelandt). To express his gratitude, Van Nieulandt dedicated his play "J'erusalems verwoestingh by Nabuchodonosor" to 'Gasper Duarte, coopman ende beminder van alle vrye consten".

Contemporaries soon referred to Gaspar's house on the Meir as "the Antwerp Parnas," in reference to the mythological Mount Parnassus where the muses lived. Anyone visiting the Duartes' home were immersed in an artistic bath. Art was on display everywhere: Gaspar Duarte laid the foundation for an exceptional collection of paintings that his son Diego would continue to grow. But above all, there was music!

The house concerts of Gaspar and his daughters

The residents at the Antwerp Parnas had at least five harpsichords and virginals, as well as a claviorgan (a combination of a harpsichord and an organ). Gaspar Duarte (I) maintained excellent contacts with the Antwerp-based harpsichord makers Joannes Ruckers and his cousin and pupil Joannes Couchet. He even advised them on the design of their instruments (although Couchet in particular followed the advice given). The Ruckers-Couchet family built perhaps the best harpsichords and virginals of the 17th century. Moreover, there was an abundant repertoire for instruments at the Duarte home: around 1628, Gaspar (I) likely had the so-called Messaus-Bull codex compiled, a thick manuscript containing keyboard music primarily by the English composer John Bull.

Gaspar (I) had a good singing voice and played violin and harpsichord, among other instruments. His children shared this musicality, and that created possibilities. Once his daughters were old enough, Gaspar organised house concerts at which he performed together with his daughters Leonora, Catharina and Francisca.

In a letter, now preserved in the Royal Library at The Hague, Gaspar (I) describes to his close friend Constantijn Huygens how one of these concerts, given in the autumn of 1640, went (freely translated):

We sometimes organise a house concert with a small instrumental ensemble, as we performed to Miss Anna Roemers Visscher, namely with three instruments that are ideal for the three girls, the spinet, the lute and the viola bastarda, and me on the violin for the third dessus voice; and for the singing: a lute and the violin together with singing by my two daughters and sometimes two voices with a bass that I sing, with the spinet or the theorbo for the little madrigals from the book.

Dutch poet Anna Roemers Visscher wrote a poem in praise of Gaspar's musical qualities after the concert, rating him higher than Orpheus and Amphion, the two greatest musicians of Classical Antiquity.

Those who were privileged enough to attend a house concert always left deeply impressed.'[The Duartes] form a beautiful and harmonious consort of lutes, violas, virginals and voices,' wrote William Swann. 'I already rejoice in the music-making in the house of the noble Mr. Duarte, because I have only experienced such music in Venice in the company of Claudio Monteverdi,' enthused Giuliano Calandrini. Margaret Cavendish (who lived at the Rubenshuis with her husband William between 1648 and 1660) described in a letter how she enjoyed the Duartes' company: 'Their company always puts me in a cheerful mood'. And Béatrix de Cusance noted in a letter how 'the dear and incomparable Francisca performs rare and extraordinary things for us'.

We can see in Gaspar's letter to Constantijn Huygens, quoted earlier, how the Duartes performed the music in various ensembles. Leonora and Catherine were primarily known as singers. Francisca was praised in letters from the Huygens family and from Béatrix de Cusance for her qualities as a harpsichordist, with her skills compared to those of French virtuoso Jacques Champion de Chambonnières. The daughters also played lute, theorbo, viola da gamba and viola bastarda.

There was a wide variety of music performed, including vocal and instrumental works by contemporaries from England, France, Italy and the Low Countries, composed by John Bull, Girolamo Frescobaldi, John Coprario, Thomas Lupo, Michel Lambert, Nicholas Lanier, Guilielmus Messaus and Joannes de Haze, among others. As a close friend, Constantijn Huygens regularly contributed to the house concerts by sending his own compositions. In 1647, he had a collection of Latin, French and Italian songs entitled Pathodia Sacra et Profana published by the Parisian publisher Ballard. The Duartes promptly received a copy, enthusiastically performing the songs.

Some members of the Duarte family also composed themselves, but Leonora was the only one whose music has survived: a manuscript (Christ Church College, Oxford) containing seven five-part sinfonias that Leonora composed in the style of English consort music of the late 16th and early 17th centuries. The works were created during her brother Diego (II)'s time at the English court.

Diego Duarte (II)

In 1632, Gaspar (I) and his sons Diego (II) and Gaspar (II), following the example of many Antwerp citizens, including Anthony van Dyck, left for England. Like other Flemish merchants, artisans and artists, they hoped for commissions from the ostentatious court of King Charles I. It paid off: in 1635, the king appointed Diego Duarte (II) as 'Jeweller in Ordinary', his permanent court jeweller.

In England, Diego joined the landed gentry after the king gave him an estate with associated rights in exchange for arrears. In the court circles, Diego became acquainted with important artists, patrons and noblemen. These included the Cavendish family and the court composer, painter and art collector Nicholas Lanier. Diego discovered the play The Deserving Favourite by Lodowick Carliell (1629) in England. Diego would later translate and adapt it into Den weerdigen gunsteling which was performed at the Chaplain's Theatre in the Main Square in Antwerp around 1685.

In 1642, Diego asked for leave and returned to Antwerp. Meanwhile, the English Civil War had broken out. The king was captured and ultimately executed, and many royalists, including the Cavendishes, Nicholas Lanier and heir to the throne, Charles II, fled to the continent. All were welcome at the Duartes'. In the case of the Cavendishes and Nicholas Lanier, the result was many evenings of music.

Gaspar Duarte (I) died in 1653. A requiem mass by Philippus van Steelant accompanied his funeral in Saint James' Church. Diego Duarte (II) headed the family business after that. He built a network stretching from Amsterdam to Paris, from London to Goa. The Dutch stadtholders, princes of the Habsburg Empire, Louis XIV of France: all found their way to Diego's firm. But they also called on him even when they didn't need jewellery. In 1676, Stadtholder William III of Orange (the future king of England) held secret consultations with his Grand pensionary in Diego's vast art room. And Albertina Agnes of Nassau commissioned Diego to arrange the purchase of several paintings.

Painting was one of Diego's passions. The painter Pieter Thys was a close friend, and he was likely on friendly terms with other painters. But above all, Diego was a collector. Flemish, Dutch and Italian masters were his preferred works. He had over ten works by Rubens, and collected a dozen works by Van Dyck. He also had works by Brueghel, Titian, Raphael, Parmigianino, Dou, van Verendael, Elsheimer, Moro, Holbein and Massijs, among others. Diego also owned a Vermeer (possibly Young Woman Seated at a Virginal), the first outside the Republic. At its peak, the collection featured around 200 works, most of them of very high quality. (These days, the paintings can be found in the Prado, the Louvre, The National Gallery, the Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp and the Mauritshuis, among other places.)

But like his father, Diego's overriding passion was that of music. He supported composers such as Joannes de Haze. The latter dedicated a collection of violin music to Diego in 1681. Less than a year later, de Haze was one of the founders of Antwerp's first commercial opera, the Chaplain's Theatre. But Diego also composed himself. Among other things, he set lyrics by his friend and neighbour William Cavendish to music.

On 26 March 1663, the mathematician Christiaan Huygens (a son of Constantijn) wrote in a letter how Diego had composed a piece of music for "the feast day," namely Easter (and in 1663 not the Annunciation which normally falls on 26 March), a day earlier. '[A] 'Piece de Devotion avec des Parolles Flamendes composeé d'un Juif, sur l'air d'une Sarabande,' which 'to tell the truth must be somewhat unusual,' replied Susanna Huygens, Christiaan's sister. A Jew composing music about the resurrection of Jesus Christ: demonstrating how easily the Duartes transcended religious boundaries.

Diego composed further works of Catholic music. In 1684, he completed his composition to set music to Antoine Godeau's psalms, the Paraphrase des Pseaumes de David (1648). The composition took more than a decade to complete. Although Diego considered publishing the work, he ultimately decided not to. The music is now lost, as are all of Diego's compositions.

Less and less music

From the 1670s onwards, things became increasingly quiet in the Duarte home. None of the children of Gaspar (I) ever married. Leonora, Catharina and Francisca died in 1678, perhaps during the plague epidemic that also claimed the life of the painter Jacob Jordaens, among others. Gaspar (II) and Isabella died in 1685. Constantijn Huygens died two years later, thereby ending the musical correspondence. Diego fell ill, and a cousin from Amsterdam, Constancia (Rachel), and her husband Manuel Levy Duarte, temporarily moved to Antwerp to look after Diego.

With the death of Diego Duarte (II) on 15 August 1691, the Antwerp branch of the family came to an end. Constancia and Manuel sold the house and most of the art collection. The music and musical instruments disappeared without a trace. Only a letter book from Diego (II) survived (partially) to the present day. The memory of the artistic Duartes is slowly but surely being lost in Antwerp.

Music as a universal language

Why did the Duartes attach so much importance to the arts, especially music?

Music was part of a good education in the 17th century. Keyboard instruments were particularly suitable for women, while plucked instruments such as the lute and theorbo were more suited to men. But above all, ladies and gentlemen of standing did not want to be too showy about their musical abilities. No matter how virtuoso their playing, they did not want to be mistaken for professional musicians, because the latter played for money and had questionable reputations. It was therefore wise to be discreet about your musical ability. The Duartes walked a fine line: their concerts were house concerts and not all family members took part, but their reputation attracted a lot of visitors.

The fact that the Duartes didn't hide their love for music was due to music's unique quality: it is a universal language. Music appeals to the heart and the head, and it transcends geographical and religious boundaries. And the latter was something the Duarte family, with their Jewish roots, could put to good use.

As early as 1549, Emperor Charles V attempted to expel all conversos (new Christians) from the Low Countries. Throughout the 17th century, conversos in Antwerp were accused of practising Judaism, fortunately mostly without consequences. (Diego Duarte (I) was also accused - without consequences - in 1608).

Still, the danger was ever-present. In 1682, the Antwerp city council referred to the Jews as a 'cursed and depraved race', and there were suggestions to create a ghetto, or make Jews and conversos wear a symbol on their clothing. These statements were mostly concessions to the (lower) clergy, and the city council may never have actually intended to oppress the conversos. Antwerp was too independent, too individual and broad-minded, and the converso community played too large an economic role.

Nevertheless, that does not change the fact that persecution was always a threat to the conversos in Antwerp. Although the Duartes were closely involved in churches and Catholic charity in Antwerp (and they even composed Catholic music!), some contemporaries doubted their allegiance to Catholicism. Close friends like the Huygens family knew better: to them, the Duartes were Jewish. And that's exactly when music is a language that allows one group to talk to any other, whether Jewish, Anglican, Catholic or Protestant.

Want to read or listen some more?

- For the music rooms, city tour and music recording: click here.

- Dutch musicologist Rudolf Rasch has written several articles on the musical network of Constantijn Huygens and the Duarte family. One of his superb editions features 300 letters on music by, to and about Constantijn Huygens (2007).

- For more information about the Duartes' professional life, see Timothy De Paepe, Een netwerk van luxe (A Network of Luxury) (pdf) (2016), written for DIVA, the Antwerp museum of diamonds, jewellery and precious metals.